Transpiration - Energy Production

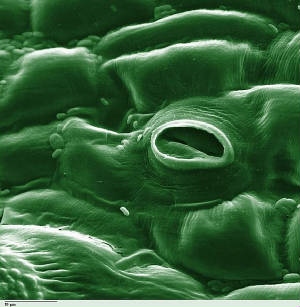

Transpiration is the evaporation of water from the leaves of plants and trees. The undersides of leaves are dotted with hundreds of tiny openings called stoma. Carbon dioxide enters the leaf through these pores, and water escapes. A mature tree may evaporate hundreds of gallons of water on a warm, dry day. The process cools the vegetation and also allows the internal flow of nutrients. The familiar veins within leaves transmit the water to the stoma. Studies have shown that the branching veins, called a dendrite pattern, are spaced out for maximum water flow. This leaf vein pattern may help design engineers build more efficient irrigation systems.

Leaf transpiration also suggests an energy source with great potential. Scientists at U. C. Berkeley and elsewhere have constructed artificial leaf surfaces made of glass. Within the glass layers are tiny, branching channels for water flow. Water is drawn into the channels by capillary action, then flows to the outer edge of the artificial leaf. There, openings allow the water to evaporate. The result is a steady flow of water along the central channel leaf stem at about 1.5 centimeter/second. The water channels also are sandwiched between thin films of metal. In electronics, this arrangement is called a capacitor. Water moving through the channels also contains small bubbles of air. Because water and air have different electrical properties, the water flow causes a slight electric in the metal plates. This electricity can be multiplied and harvested from many glass leaves.

Engineers suggest large arrays of the artificial leaves, equivalent to entire trees. These could function alongside traditional solar collectors to produce energy. Vegetation first appeared on day three of the Creation Week. Now, millennia later, transpiration in the plant world teaches us concerning energy production.

Noblin, X. and many others. 2008. Optimal vein density in artificial and real leaves. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105(27): 9140-9144.